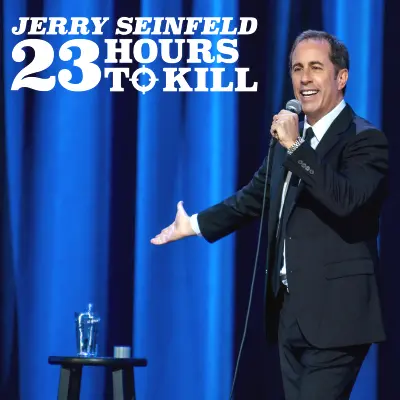

In Netflix's 23 Hours to Kill, Jerry Seinfeld comes across like a comedy machine that's broken down

-

"As a piece of stand-up — the only metric I imagine that matters to Seinfeld — 23 Hours to Kill is a smooth, solid piece of professional entertainment," Tim Grierson says of Seinfeld's first fully original standup special in 22 years. "Bounding on stage to the brassy, big-band strains of 'Come Fly With Me,' Seinfeld has fashioned his set as a classy piece of old-school Vegas showbiz. Every joke is polished, every punchline is impeccably delivered. Like with Frank Sinatra, part of Seinfeld’s appeal is his king-of-the-world swagger, his deserved confidence that he can do his job as good as anyone right now doing it. Many of the special’s bits will be familiar to those who have seen him live or on late-night talk shows. But even so, there can be pleasure in watching Seinfeld go through them with mathematical precision, setting ‘em up and knocking ‘em down. But despite the seemingly momentous fact that it’s been so long between Seinfeld specials, what’s strange about 23 Hours to Kill is that this hour doesn’t feel particularly … special. The Beacon (Theatre) is gorgeous, and Seinfeld is spry and focused, dressed in a sharp suit. But beyond some well-executed jokes, 23 Hours to Kill doesn’t take many risks or offer any deeper perspective on, frankly, anything. To be clear, I wasn’t expecting Seinfeld to somehow magically come up with a set that would address our uncertain times. (The special was recorded long before the pandemic.) But while it’s unfair to criticize 23 Hours to Kill for its inability to read the room, so to speak, the show does cast into sharp relief the frustrating anonymity of the man who conceived it. Jerry Seinfeld has repeatedly told us that he’s not a confessional comedian — that he’s not one for pathos or sentimentality. The laugh is all. But during the special, I never much felt like I was engaging with a relatable human being. He’s just a machine who dispenses zingers at regular intervals."

ALSO:

- 23 Hours to Kill is a breezy delight: "Some of you will be so grateful you’ll be reduced to blubbering wrecks, after you’ve finished laughing," says John Doyle. "No angst involved, no Trump jokes or even a cuss word. Just Jerry Seinfeld observing things and doing what only Seinfeld can do – make the mundane seem ridiculous and obliging you to nod in agreement."

- The first half of 23 Hours to Kill is great, the second half sucks: "The Seinfeld of the first half-hour is a cantankerous guy who slices through many of the most inane features of modernity with speed and precision, and he does it with such joy," says Kathryn VanArendonk, adding: "It’s remarkable how fully the dynamic changes when Seinfeld turns his eye on his own life. In much of the second half of the special, he is a schmuck in a suit who complains, mostly about his wife. He has shrunken and forcefully cut himself down to size with the blunt ax of his own self-consciousness. He has been married for 19 years, and it is exhausting."

- Seinfeld doesn't shy away from the age factor: "Most refreshing is the way age has found Seinfeld leaning into the bleak nihilism that has always laced his comedy," says Alex McLevy, "the dark undercurrent of his material now evolved past the point of misanthropy into a full-throated disgust for the human race as a whole."

- We don’t turn to Seinfeld for personal intimacies: "He is Mr. Generic," says Brian Logan, "the American everyman who exists on stage to channel our observations of, and mild frustrations with, the business of being alive."

- Weird though it may be, an average episode of Seinfeld from 1993 feels more “modern” than 23 Hours to Kill: "The new special is clean enough to keep even the most easily offended people feeling unruffled," says Jordan Hoffman. "Other than some thoughts on being grossed out by public toilets, there’s nothing in here that wouldn’t be considered PG. Not that there’s anything wrong with that — Jerry Seinfeld has never had to lean on profanity for a cheap laugh — but Jerry, George, Elaine, and Kramer’s hijinks back in the day occasionally showed blood pumping in their veins, via sexual topics or explosive anger. Nothing in 23 Hours to Kill gets a smidge over 98.6 degrees, suggesting once again that anything on the old show with fire to it was Larry David’s domain. But Seinfeld still strikes funny, and the way he hits familiar notes is more than a nostalgia act."

TOPICS: Jerry Seinfeld: 23 Hours to Kill , Netflix, Seinfeld, Jerry Seinfeld, Standup Comedy

More Seinfeld: 23 Hours to Kill on Primetimer: